Today we’d like to introduce you to Curry J. Hackett.

Curry J., we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

After my undergraduate studies in architecture, I found myself working on a massive stormwater project in Washington, DC. That time really inspired me to think critically about the relationships between cities, culture, and ecology, and eventually led to starting a design and research practice focused on creating meaningful public art and audiovisual media.

Right before the pandemic, I started teaching architecture as an adjunct, which blossomed into a wider interest in landscapes, urban design, Black studies, and an eventual return to graduate school for urban design. I now teach as a full-time professor in media studies at NYU.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

My career trajectory has been an unorthodox one: from working with civil engineers, to becoming a public artist, to architecture professor, to media studies professor and multimedia artist. Each of those transitions created a lot of space for imposter syndrome to set in, and feelings that I was being pushed to make a move that didn’t always feel appropriate or necessary at the moment. I’ve since learned to embrace those moments as opportunities to learn about myself and the world, and “doing it for the plot” has become a really productive mindset for me.

Thanks – so what else should our readers know about your work and what you’re currently focused on?

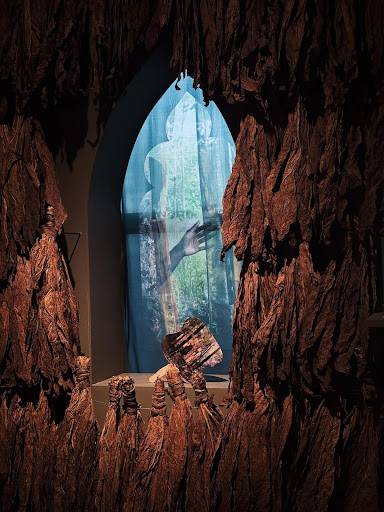

Before a few years ago, I think most folks knew me for the public art installations I had been working on in Washington, DC, and my thoughts on landscape and Black culture. More recently, my explorations in artificial intelligence have gotten a lot of attention on social media—so much so that some of my visions have been offered opportunities to be manifested as real-world experiences. The fictional scenes that I create with generative AI tools are attempting nostalgic, yet gently futuristic, moments of Black joy and agency. They take a lot of inspiration from the textures of Black life in the rural South: quilts, kudzu vines, gardens, and gatherings near creeks and rivers. Many have told me that the work is one of the most compelling use cases for AI they’ve seen, and I believe it’s because I’m ultimately trying to visualize worlds that are comforting and pleasurable for people in general, and Black people in particular.

What were you like growing up?

I was an inquisitive kid, according to my parents. I loved playing outdoors and was always bring insects, soil, frogs, and plants into the house. My mother is a retired art teacher and my father is trained in engineering, so I think I inherited creative and critical ways of understanding my world.

In middle and high school, I remember being what today might be considered an “ambivert”: someone who needs a good balance of solitude, but also thrives on lots of socializing. This was reinforced by my interest in music and playing in the band—which is both an individual and a group activity. My parents told me that it could sometimes be difficult to punish me: if television or group activities were taken away, I would simply go in my room and read and either play with (or invent) toys and games.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.wayside.studio

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/curryhackett

Image Credits

Malakhai Pearson (images 4 and 5)